by David Reavill

In the history of Western Civilization, tensions have nearly always existed between the power and authority of the citizens and that of the State. It’s easy to forget that Rome began as a Republic and only later transitioned into the Roman Empire.

Power transferred, as if on a great Pendulum, from the people to the Caesar. For Rome, this move toward autocracy was due primarily to the life and death of one man, Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus.

Tiberius grew up at a time of significant Roman expansion. What had begun as a small emerging country over four centuries before was rapidly transforming into the dominant world power of its day.

But it was not without stress. The Republic suffered from endless wars as the Romans expanded their territory. But this took a tremendous toll; their economy suffered from numerous recessions as resources were diverted to the “war machine.” Food shortages were common, as many of the middle class, called “plebs,” struggled to make ends meet.

However, like America today, the oligarchs prospered. They acquired large swaths of “Ager Publicus,” the land conquered by the Roman Legions. And while it was supposedly public land, it ended up in the hands of the Oligarchs, generally the Roman Senator Class.

Thus, the Roman aristocrats could prosper during the tough times, while the “middle class,” the plebs, suffered through an uncertain economic future. Worst of all, the lower class, sometimes plebs who had lost their small farms, endured the hardships of slavery.

As Rome continued to conquer more and more territory, as its wealth and influence grew, political power became progressively concentrated in the hands of a few.

The middle-class plebs found themselves in a giant vice, forced to bear the burdens of the endless wars and often subjected to conscription into the Roman Legion; they would face higher taxes and increasing economic uncertainty as many times their farmland was not fertile, and their access to water was limited.

There emerged from this milieu a young man, just in his 20s, who had captured the imagination of the plebs. He was Sempronius Gracchus. Gracchus was an Army Veteran who fought in the Third Punic War and the Numantine War, quite an accomplishment for one so young. Gracchus had all the qualities to make a fine Roman Leader.

He was himself a Pleb; he understood the Plebeian point of view and could present their case before the Roman Senate. It was just these attributes that the Roman Senate must have observed as they appointed Gracchus as “Tribune of the Plebs.”

It was an important position for Gracchus, placing him squarely between the concerns and anxieties of the Roman middle class (the Plebs) and the Central Powers of Rome, the Senate.

Gracchus became the focal point in this pivotal political conflict for the Roman Republic. Tremendously popular among the Plebs, he was seen as a force to be reckoned with and a potential threat by the Central Powers.

Immediately, Gracchus took up the mantle of land reform. With each subsequent War, the Roman Legion gained new land, land that by rights was public (Ager Publicus), but always seemed to end up in the hands of the oligarchs. It was the one area the Roman oligarchs had used to build their wealth and, ultimately, their power. Land reform was a direct threat to the entrenched oligarchs in Rome.

Not afraid to fight, Gracchus pushed for land reform with all his might. He had a fellow Tribunal fired when he opposed Gracchus’ reform; he even defied the Roman Senate by signing a treaty without Senate confirmation. In 133 BC, he prepared to present his Land Reform plan to Rome. Unfortunately, the bill was vehemently opposed by a fellow Tribune and failed to gain any traction.

But this was enough to show the Roman Senate and all the oligarchs that this young man was a danger to the ruling establishment. Gracchus was incredibly popular and unafraid to use unconventional methods to push his agenda. In short, Gracchus didn’t understand his “place” in the Republic. He would have to be dealt with.

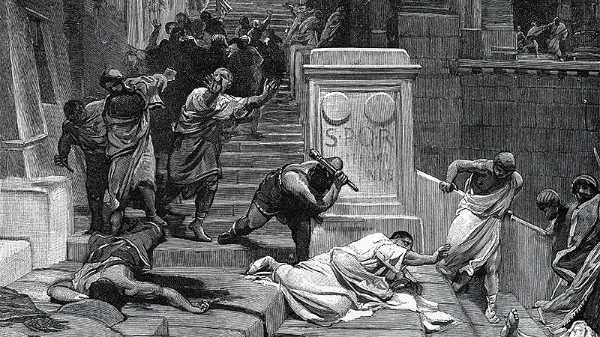

In what has become standard procedure among the unscrupulous, a riot broke out, and during the riot, Gracchus was murdered. Just who was responsible, we’ll never know. That’s the genius of using a riot to dispose of someone. Just who authorized the “hit” is, still to this day, mere speculation.

While the assassin’s identity remains a mystery, most Historians now agree on a couple of conclusions. With the death of Gracchus, the reform that the Plebs sought was finished. There would be no land reform; this was reinforced a decade later when Gracchus’ brother also tried to pass land reform, but he, too, was murdered, putting a final end to any hope of reform.

But even more, Gracchus’ death marked the ultimate end of the Roman Republic. The very thing that had made Rome great, allowing nearly all the members of society to have a voice, was now extinguished, snuffed out. From this point on, the Plebs would not be heard from again.

Roman political power would continue to be concentrated in fewer and fewer hands. Ultimately, 160 years later, one man, Gaius Julius, Caesar Augustus, became the first Caesar in a long line of total and complete dictators.

Sometimes, the Destiny of the Republic rests upon the Fate of One Man.

Subscribe to the Daily Newsletter